From Dog Sports Magazine, March 1984:

The Origins of Police K-9

Chief Kimball P. Vickery

Mt. Angel, Oregon, Police Department

The Night Watcher

Clk to enlarge

I have been an active police service dog handler and trainer for the past 16 years and have, during this time, given numerous presentations on police service dogs to school children, civic groups, and other interested organizations. One question which is always asked is the one concerning the origin of police dog programs. When I began this interesting and rewarding specialty in 1968, I decided to do some research into its history, anticipating such questions during my presentations and not wanting to appear overly ignorant on the subject. In one informational booklet, I read that all organized police service dog programs originated with a program established in Gent, Belgium, in 1899. Although I could locate no further information on the Gent program, I continued to convey this fact during the course of my presentations. A few years ago, I began corresponding with Sgt. Erik Verwilst, a Belgian gendarme stationed in Gent, and was fortunate enough to be able to visit him at his residence in Gent last summer. Since the mystery behind the Gent police dogs had been in the back of my mind for many years, I decided to ask Sgt. Verwilst to locate for me any available documentation on the subject from the Gent Police archives. In response to my request, I was presented with numerous photographic reproductions of original photos and photocopies of original documents on the subject in English, French and German, including a booklet in French written by the founder of the first police dog program himself, Chief Commissioner (Chief of Police) Ernest H. P. Van Wesemael in 1910. All of this documentation was provided through the courtesy of Chief Inspector Roger De Caluwe of the Gent City Police, who obtained this information through his departmental archives and the Gent Public Library.

Dog Sports Magazine

Clk to enlarge

It is doubtful that these original dog-handler pioneers had any idea that the concept they originated in 1899 would still be a vital part of world law enforcement nearly 90 years later. Every citizen who has ever had his stolen property recovered by use of a police service dog, every parent who has ever had a lost child found by a police service dog, and every police officer who has ever been protected from serious injury by a police service dog, owes an everlasting debt of gratitude to these 10 men who had the fortitude to initiate a concept, which, at the time, was unheard of in the law enforcement field. This, then, is their story as I have condensed it from over 15 contemporary booklets and newspaper articles written in three different languages. Chief Van Wesemael, Gent Police Chief from 1888 to 1915, even then was faced with the same problems which plague most police a demonstrators today, that is a rising crime rate, numerous unsolved major crimes, and a lack of funding to hire additional personnel to combat this rapidly deteriorating situation. When the Gent burgomaster (mayor) refused him additional funds, Van Wesemael made the statement, "If you can't give me more policemen, then give me some dogs." The mayor agreed, since the cost of the dog program, as outlined to him by Van Wesemael, was substantially less than the funding of an additional 100 policemen, as was the original request. It remains unclear just how Van Wesemael had gained experience in training dogs. It can only be assumed from what little information is available on Van Wesemael's personal life that he was at the time actively engaged in breeding and training Belgian herding dogs and felt that if such dogs could be trained to herd cattle and sheep, they could likewise be easily trained to "herd" criminals. Perhaps he had been experimenting with this theory in private and was convinced that his concept would work. So, in March of 1899, three dogs of the Belgian herding variety, resembling our present-day Bouviers, were acquired for Chief Van Wesemael by the Gent city veterinary officer, and the training of these dogs, along with that of their policemen handlers, was personally begun by Chief Van Wesemael, who eventually turned this training task over to qualified subordinates. Shortly before Christmas of 1899, 10 dog and handler teams were at work. The dogs were initially utilized at night in the city's high crime neighborhoods, along the waterfront, and in the wooded outlying sections of the city. Their success in diminishing the problem at hand was nearly instantaneous. Night crimes, previously both numerous and serious in these sections of the city, fell off two-thirds simply because the employment of the trained dogs was enough to render doubtful certain nefarious plans.

Gent Dog Squad

Clk to enlarge

After 10 months of trial, the most conservative members of the Gent city council became enthusiastic over these new police "recruits" and voted additional funding for more dog patrol teams to be used in other areas of the city. Chief Van Wesemael wasted no time and soon there were 30 big, powerful dog "policemen" on duty and working with surprising efficiency. They would take a new handler over his night beat with a zeal, a thoroughness, and a relentless, systematic vigor that would kill a lazy officer. They knew their work and could and did correct many an officer who was a novice at this type of assignment. As far as their off-duty time was concerned, he animals were given every care. They were given baths once a week and their kennels were disinfected regularly and periodically whitewashed. For the first 15 days new recruits were kept in their kennels and taught merely obedience. Military brevity, combined with unvarying kindness, marked all orders. In fact, any human member of the force striking a dog was subject to instant dismissal. In due time, certain training officers would take the recruit dogs out on patrol with chosen veteran dogs. All dogs began duty at 10 p.m. and ended their shifts at 6 a.m. They were never allowed to leave their kennel/training compound, located in the heart of the old city, during daytime, and on no account were they allowed to become acquainted with outside personnel or civilians. They were fed twice a day: at 7 a.m. and at 7 p.m. Their fare was a type of soup, with a little meat, some rice, and a very nutritious biscuit known as "kneipp." Each ration weighed about three pounds. During patrol duties at night, each dog received a large slice of bread, and so carefully were their needs and capacities studied, that the animals never appeared tired or spiritless upon returning to the kennels after a lengthy and often dangerous tour of duty. When a recruit began to show aptitude under training, the handler/trainer to whom he was assigned took him out on patrol, giving him scraps of meat and an occasional bone, and in this way emphasis was placed on the lesson the dog was intended to be taught, namely, that only people in police uniforms were to be trusted. All other humans were to be eyed with suspicion, if not with positive ferocity. During this time, the recruit was also led to every nook and corner of its future beat for the purpose of familiarization. For one month this work was conducted three or four hours a night under all weather conditions, the hours of duty being gradually increased to the standard eight. The final stage of the recruit's training involved the attack, or rather pursue-and-hold, training. The dogs were taught by means of dummy figures made to resemble thieves and other characters the dogs would be likely to encounter. Great patience was needed as the dogs had to be taught to seek, seize, and hold a suspect without hurting seriously. The first step was to hunt out a quarry attempting to hide, which was soon learned. Up to three months of this type of training was required before a recruit was allowed to take its place for service. The dogs were also taught to seize their quarry in water, to overcome obstacles, and to save people from drowning. Their uniform consisted of a leather collar strongly bound with steel and armed with sharpened metal points to repel attempts at choking. They were also issued strong leather muzzles to be used for special occasions where the ultimate of their aggression training was not required.

Gent Police Bouvier

Clk to enlarge

By 1906, about 60 police dog/handler foot teams were on duty during night time in and around the city of Gent, which was divided into 120 sections, so arranged that each team could readily count on its neighbors' support if the occasion should arise. An alarm was sounded, not by a whistle, but by a small, shrill horn with which every handler was equipped and with which every dog was familiar. Careful checks were made upon the dog handlers by roving supervisors, ensuring that each team made their complete rounds into every yard and alleyway on their beat. However, even if a particular officer-handler were inclined to shirk his responsibilities, his dog partner would make certain that there was not time for malingering. Relating the achievements of his dogs, Chief Van Wesemael would frequently use as an example an arrest once made by one of them named "Bear." One night on patrol, Bear and his handler came upon five drunken thugs attempting to wreck a saloon. The men were creating a great disturbance and it was surmised that they would also make a resolute resistance to any efforts on the part of police officers to quell this disturbance.

Bear's muzzle was removed and the dog sprang forward without a sound. By the time Bear's handler arrived at the scene on a dead run, Bear was clutching one of the troublemakers by the leg, the other four having apparently fled. As the handler arrived, Bear gave up his prisoner and was off on the trail of the fugitives. The handler followed with his prisoner in irons, guided by a series of short, sharp barks. Shortly he came upon the other four, who were at bay against a store front attempting to keep the dauntless Bear from "tearing them to pieces." Thoroughly frightened, even completely sober by then, the men quickly agreed to give themselves up if Bear were controlled and muzzled. This was promptly done, though not without a little protest from Bear himself, and the procession started towards the central police station and city jail, with the victorious Bear, now at liberty to express his joy, barking and racing around his prisoners, exactly as if they were a flock of sheep. Chief Van Wesemael, in chapter 13 of his booklet, Le Chien Policier A Gand (The Police Dog of Gent), published in 1910, outlines several truisms applicable to his canine training endeavors. In conclusion, I am presenting a translation of these truisms in order to show the similarities between his viewpoint on canine training and the generally accepted viewpoint of today's police canine trainers.

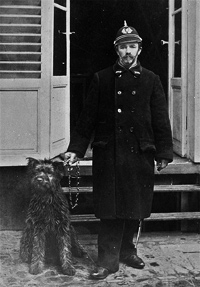

Gent Police Chief

Click to enlarge

"Before this small brochure is ended, we feel it would be useful to list a few recommendations for those who wish to start a service (police dog) as it exists in Gent.

" . . .The dogs should, as much as possible, be given one-syllable names. The calling of their names can then be done in a single tone and consequently in a more energetic manner.

"... It is preferable to select dogs with dark, or dull, colorations. Such dogs cannot be seen as readily by criminals in the darkness and therefore are not as subject to being injured by thrown projectiles and brandished weapons, or fired upon.

"... It is almost superfluous to advise that the handler to whom a dog is entrusted must have a predilection for his animal that develops rapidly into a deep, mutual affection. The handler must look upon his dog as a companion ready to sacrifice himself for the handler on a moment's notice.

" ... As a final word, if one becomes discouraged over the first obstacles experienced in estabishing a program such as ours; if the field officers and/or their administrators who have elected to institute this new concept do not enter into their program wholeheartedly with the desire to succeed, it will be labor lost. Not the slightest detail can be neglected, neither in the selection of animals and their training, nor in the choice of officers to handle these dogs."

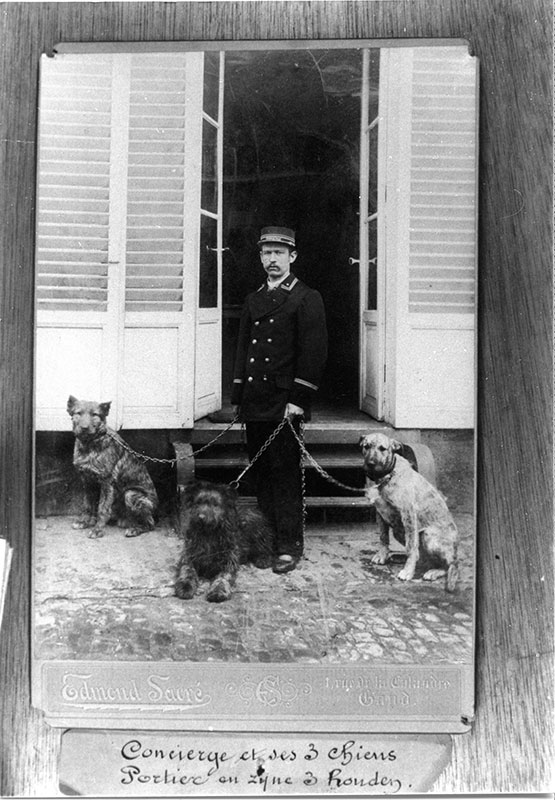

Three Gent Police Dogs

Click to enlarge

As a final note of interest, several police canine programs in the U.S. and Canada were begun shortly after the turn of the century following visits of department representatives to Chief Van Wesemael in Gent. In fact, it appears that several Gent-trained dogs were purchased by these American officials in order to start their programs.

Among those departments which original correspondence clearly shows had ties with the Gent program are: New York City, 1908; South Orange, New Jersey, 1907; Muncie, Indiana, 1908; and the Grand Trunk Railway System Police, Quebec, Canada, 1903.

Photos courtesy of the Gent Police Dept

Copyright Kimball P. Vickery

Web page by Jim Engel

Revised June 2015